MissingSchool was featured in an article from Women Business News. To view the original article click here.

Around Australian more than 60,000 children miss school often, or for longer periods, due to serious illness or injury. This obviously impacts on their education, but social isolation and disconnection from friends and peers causes even greater problems. This number has increased exponentially during 2020 because of medical vulnerability related to the current pandemic.

Megan Gilmour one of the founders of MissingSchool knows this from personal experience. Megan’s son was 10 years old, when he was diagnosed with a serious illness that would keep him out of school for almost two years.

“His absence from school obviously left a gap in his education, but this wasn’t just academic, it was also social. When kids are sick, life becomes very isolated and they experience painful things – a lot of horrible things that few can relate to,” says Megan.

“When he did eventually return to school it took him a long time to reengage with his learning, the environment and his school peers.”

“Many kids who have chronic illnesses find the transitions in and out of school, or the return to school, to be very difficult and this has a range of long term implications,” says Megan.

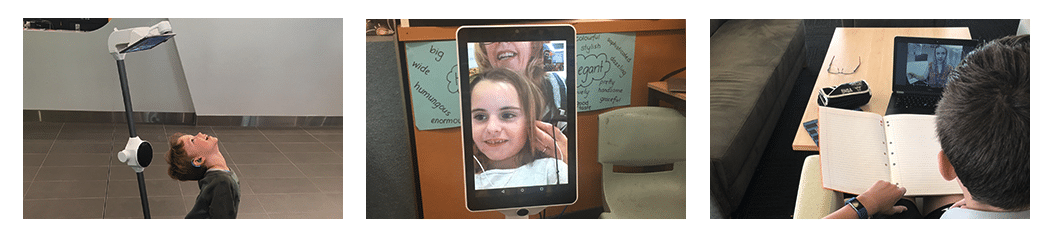

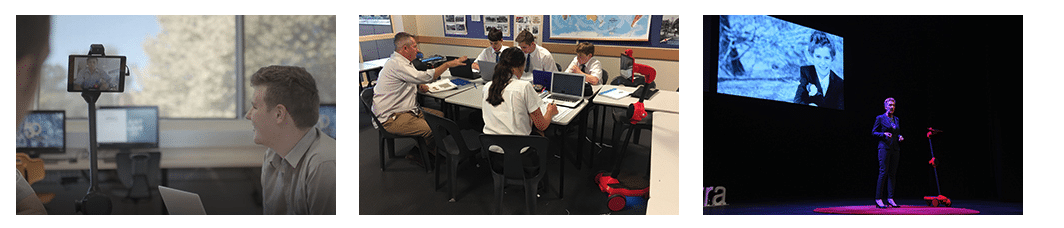

MissingSchool was launched in 2012 by Megan and two other Canberra mothers, to help seriously sick kids connect to their regular schools and get their special learning and social needs met. Since 2017, MissingSchool has been using robots to put sick children back in their classrooms via telepresence.

Megan says that schools find it hard to provide support to kids who aren’t physically in the classroom. It is a complex issue and, while our education systems are responsible for solving it through legislation and policy guidelines, there are myriad challenges to overcome.

“We started MissingSchool by initiating some very strategic research. We then released an Australian-first report at Parliament House in 2015 and received support from the Prime Minister and the National Children’s Commissioner.

The Commonwealth followed that up with a study finalised in 2017, which was released late last year,” says Megan.

Megan won a Churchill Fellowship in 2016 to investigate this issue in six countries and to position responses in Australia. She found that similar problems exist around the world. While on the Churchill Fellowship, Megan pitched the idea of a national telepresence robot pilot to the St.George Foundation.

“We couldn’t find any systematic solutions to the problem in Australia, which put sick kids into their own classrooms, so we pitched the robot idea,” says Megan.

“We were thrilled to secure $600,000 and have just completed our three-year pilot. We have worked across Australia through hospital systems and education departments to pilot this idea of two-way digital connection. We are working across all school systems, and all illness groups, from K to 12. Public education systems in all states and territories have operated the robots on their networks, which is phenomenal.”

The robot pilot was first launched in the ACT through the Centenary Hospital for Women and Children and then rolled out across Australia.

Megan says that the response to date has been incredible across the board. “Technology is always a challenge and it has its up and downs, but the positive impact of connecting kids back to their schools and peers is undeniable.”

Megan says the benefit for peers is also obvious because they are often concerned about their friends when they are not at school. “There is always a great reaction when kids dial back into the classroom.”

The plan for this year is to focus on working with governments to put policy in place to scale and support sick students to stay connected to school. To date an estimated 2,850 classmates have been reconnected through the deployment of over 100 robots, 285 teachers have been trained in their use, 950 teachers have been observers.

The current health crisis has focused the world’s attention on the challenges related to isolation, education and work. There has never been more empathy for the plight of students confined and how to maintain their education and social connections.

In the beginning, the organisation trialled a number of robots, and settled on the Ohmni, manufactured by OhmniLabs in the US. MissingSchool’s work spun off a ‘sister’ social enterprise, Robots4Good. Cofounded by Megan and Canberra entrepreneur, Marcus Dawe, Robots4Good holds the distribution rights for the Ohmni robot in Australia and New Zealand.

“We have begun to use telepresence robot technology to address isolation in a range of other contexts – think aged care, disability, and health care settings,” says Megan. Social distancing in COVID-19 has increased demand for telepresence robots, globally. We work closely with OhmniLabs on all aspects of deploying this technology, and to operate Ohmni robots-as-a-service.

While MissingSchool currently focuses on supporting kids with physical illnesses, she notes they can also experience anxiety and psychological stress. Megan says that the organisation is exploring ways the robots can also be used in cases where children are experiencing mental illness, where there is special support from the school and family, or referring agencies. The robots have been successfully tested for young people with quadriplegia.

“We do all of the placement activities from a remote location, says Megan. We do discovery calls with family and the school and decide together on whether it will be suitable for the child. Then we continue with a series of work flows to place and integrate the robot until it’s up and running, and provide troubleshooting and monitoring activities to support. We then step back until we are asked to facilitate an exit.”

Megan went on to say that MissingSchool’s processes are based on three years of experience in what is probably the largest mobile telepresence robot initiative in this context in the world. As well as for kids, we work to ease the additional workload on teachers. “When the robot works well (which isn’t always the case) it is relatively easy and low maintenance for both student and teacher. We schedule check-ins with parents and teachers to see how the placement is going. We have comprehensive monitoring and evaluation processes to capture data and learn lessons for improving the experience for all parties.”

This year MissingSchool will establish a sustainable funding model so that parents will never need to cover the costs of keeping their children connected to the classroom during absences. National research will soon be released to socialise the results of the telepresence robot initiative and share lessons and information across Australia and overseas, for systemic change. The organisation has collected around 2,000 data points, with the weight of evidence resting on the robot’s role in supporting social and emotional connection.

“Our ultimate aim is that students with serious illness or injury can maintain real-time connection to their regular schools, as business as usual, so they have the hope of a future worth living,” says Megan.