MissingSchool was featured in an article from The Age. To view the original article click here.

Seven-year-old Ayla hasn’t been able to go school for months: a chronic illness and chemotherapy keep her out of the classroom most days. But when millions of other students were forced to learn from home during the coronavirus pandemic, the year 2 student finally felt the same as everyone else.

“It was a lot easier for Ayla during that time,” her mother, Prasadi Pilosof, said. “She wasn’t the only one who wasn’t there. Everyone did Microsoft Teams catch-ups with the teacher, and it was an even playing field.”

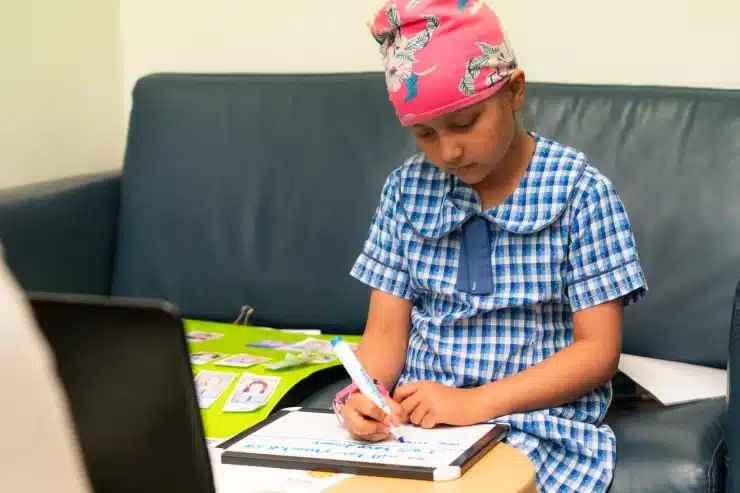

Seven-year-old Ayla learns from home using a telepresence robot, which connects her to her classroom.

For many immunocompromised or disabled students, the coronavirus pandemic has raised the bar for what a more inclusive approach to education could look like.

“Before, we got some work emailed to us, online [material] from the hospital school or we found work for her ourselves. The school was supportive but there wasn’t a lot they could do because the work was face-to-face focused,” Ms Pilosof said.

But the learning-from-home period has made Ayla’s school more aware of providing remote support, Ms Pilosof said. Her teachers have continued to update the week’s spelling lists online, and Ayla can now upload her assignments from home through Google classrooms.

Another important part of Ayla’s connection to school has been a telepresence robot that attends class on her behalf and livestreams lessons back to her at home, provided by charity MissingSchool.

Ayla’s telepresence robot lets her see into the classroom when she cannot attend. MissingSchool, the provider, is calling for the robots to be more available since the pandemic has kept more children at home.

Since term four last year, Ayla has been able to attend maths, English and singing lessons while she controls the robot remotely and interacts with teachers and friends.

“She’s got a smile on her face and lots of best friends. She’s happy to see them in class even though she can’t in person,” Ms Pilosof said.

MissingSchool co-founder Megan Gilmour said the pandemic had helped schools realise their responsibility to support children who could not be in classrooms due to health issues.

She said urgent funding should be directed to technology, such as the telepresence robot, for the 60,000 Australian students who regularly miss school due to illness, as well as their siblings who have recently been absent from school due to the risk of bringing COVID-19 home.

“The pandemic saw [most] families experiencing some of the difficulties that the families of children with serious long-term illness face, with isolation, difficulty accessing lessons, concerns for health, uncertainty and financial pressures,” she said.

However, reopening schools had meant some of those students lost a feeling of equality once again.

“There is no longer any doubt that children should stay connected to their learning and peers when a health crisis means they can’t physically attend,” Ms Gilmour said. “There is so much to do and so much demand.”

Mary Sayers, chief executive of Children and Young People with Disability Australia, said the same considerations needed to be made for young people with disabilities who might have benefited from learning with technology during the pandemic.

“This group already face multiple barriers and difficulties in accessing inclusive education, support for reasonable adjustments and the same curriculum as their non-disabled peers,” she said.

“We do not want students with disability to lose any of the positives or gains made during the home isolation period. This will require considerable effort by schools and the education system to identify and plan for a more inclusive approach to the recovery and beyond.”