At just 11 weeks of age, Macy Rawnsley, now five, was diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder that few doctors in Australia had even heard of, let alone treated.

“Macy’s condition is extremely rare, with only around 200 cases in medical literature worldwide,” says Kate Rawnsley of her daughter’s generalised arterial calcification of infancy (GACI) diagnosis.

The progressive, lifelong disease causes an abnormal build-up of calcium in the walls of arteries, which can lead to critical blockages, restricting blood flow to organs – in particular, the heart – and potentially result in stroke, cardiac arrest, and death.

“Most doctors you talk to have never heard of GACI, which isn’t surprising given we’re talking about a disease that, until recently, children really didn’t survive past six months of age.”

Back in 2018, Macy came close to being a statistic.

The Rawnsley family was told she was “very unlikely to survive the night” when they arrived at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital, unaware of the challenges that lay ahead.

“The disease process of GACI begins in utero, so babies can either miscarry, be born preterm or be born with issues in their heart or in any organ, but particularly the heart seems to be commonly affected,” Kate says.

“Macy was born at term and did have some minor heart rate issues during the birthing process, even though nothing was picked up on her ultrasound. When she was one week old, we noticed symptoms that, in hindsight, were heart related.

“We kept taking her to GPs and the local hospital, but I wasn’t getting the answers I needed, so I drove her from Bendigo to Royal Children’s Hospital, and when we got there, she was in peri-arrest, showing signs of being about to have a major cardiac arrest.”

Macy rallied that night and the next, enabling further medical investigations and, ultimately, her GACI diagnosis.

“At that point, the hospital medical team sat us down and essentially explained that there was no chance of survival – that the disease is fatal, and Macy was not in a good spot’,” Kate says.

“She was incredibly fragile but continued to rally. So, they decided to start treatment, while warning us that the treatment may take weeks to months to take effect, and they didn’t know if they’d be able to keep her alive that long.”

Macy spent nine weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and three months on the cardiac ward at Royal Children’s Hospital before being discharged under its “hospital-in-the-home” service, involving the Rawnsleys moving from Bendigo to a nearby apartment for six months, with the support of not-for-profit, HeartKids.

By the time they returned home to Bendigo, Macy had passed her first birthday milestone and, as a possible knock-on of medication to tackle calcification in her arteries and blood vessels, needed to wear a full spinal brace for four months due to a “crumbling spine”.

“The treatment aimed to get rid of the calcification, but it’s obviously not selective and they think it was also drawing out calcification from the bone itself, and that’s why she had quite a severe reaction with lack of bone density,” Kate says.

“Once Macy learnt to sit up, the effects of gravity caused multiple spinal fractures and a couple of rib fractures and she was obviously in excruciating pain, but given she was still a baby and couldn’t talk, it took a little while for them to work out exactly what was going on.”

Today, Macy continues to defy all odds, and is gearing up to start Foundation Year at St Francis of the Fields Primary School, in 2024, with the game-changing assistance of a MissingSchool telepresence robot beaming her into the classroom when she can’t be there in person.

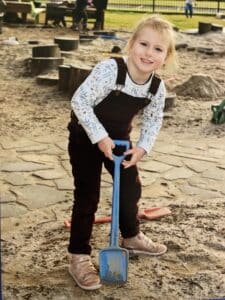

As Kate explains, while her “little, want-to-be botanist” looks like any other happy, healthy kid, the progression of GACI means she lives with dilated cardiomyopathy and reduced bone density.

In the past six months, Macy has also developed complications that impact normal blood flow to her brain, likely requiring cerebral revascularisation surgery before the end of the year.

“This progression of the disease is rare upon rare,” Kate says, adding that medical literature suggests “GACI children might have calcification in the blood vessels in or around the brain but, over time, it likely goes away and doesn’t cause any associated symptoms or problems”.

“We thought it was just Macy’s heart that we were dealing with, so this is all new and annoying, and we’re in a bit of a write your own rule book situation at this stage.

“The biggest issue for Macy is that her carotid arteries, which run up her neck and are responsible for the main supply of blood inside her brain, aren’t doing their job properly. To compensate, her vertebral arteries, which normally supply the back of the brain, are working harder to also send blood to the front and sides of her brain.

“The arteries do a pretty good job when Macy’s at rest but can’t cope with extra metabolic demand if she exerts herself a little too much or comes down with a virus.”

To further complicate matters, Macy has what’s known as GACI Type 2, which occurs in only 10 per cent of patients diagnosed with the disease, characterised by a genetic mutation of the ABCC6 gene vs the ENPP1 gene (in more commonly diagnosed Type 1 cases).

“The ABCC6 deficiency causing GACI has only been discovered in more recent years, so we’re in uncharted territory as Macy gets older. Most adults that have a problem with the ABCC6 gene have Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum (PXE) – a disease that is different from GACI so comparisons for Macy are difficult,” Kate says.

“We’re now starting to see a handful of kids around the world, the same age as Macy, who have this ABCC6 mutation and are developing neurological symptoms.

“There’s a little boy in Italy who had brain revascularisation surgery last year, and a little girl in the United States who’s having fairly significant neurological symptoms, and a couple of others who are starting to show symptoms.”

For Macy, neurological symptoms present in the form of migraines or transient episodes of weakness down the left side of her body. Sometimes very subtly affecting the left side of her face, but more commonly showing up in her left leg.

“When you see her in person, she really does look like a normal kid,” Kate says, quickly adding that a cold or flu virus can put Macy in hospital – as can playing tiggy, being bumped, falling, or simply walking too far.

“When Macy has a temperature, it obviously changes how her vessels work, makes her heart work harder, and further compromises the flow of blood to her brain.

“We don’t exactly know why, but one or two weeks after she’s had a virus, she then tends to have a post-virus TIA [transient ischemic attack], which lands her back in hospital again. I guess some kids get post-viral rashes, while Macy has what’s essentially a mini stroke.”

At the start of 2023, Kate felt Macy was well enough to attend kindergarten (co-located at St Francis of the Fields Primary School), only to watch her daughter’s growing disappointment as she missed large chunks of the year due to medical appointments, procedures, and hospitalisation during “a winter of terrible viruses”.

“It’s been really hard for Macy to establish close peer connections because she just couldn’t get a consistent run of attendance. She’d start building a friendship, then be away for a few weeks, come back, and find it was like starting all over again.

“Each time this happened, she felt a bit less confident going back to kinder. She didn’t have those default peers to go to, and friendships sort of evolved while she wasn’t there.”

Moving forward, Kate says there’s no doubt in her mind that Macy’s continuous access to school, including connection to teachers and peers from hospital or home, via a MissingSchool telepresence robot, will prove lifechanging on multiple levels.

“Macy’s condition is unpredictable, so it’s hard to know if she will be able to attend something she’s been looking forward to for weeks – like a Disney dress-up day at kinder, which she’d planned out the whole costume for, and then a procedure got booked that day.

“She also missed Book Week Parade and going across to ‘big school’ to meet next year’s Primary School buddies because she ended up being hospitalised – whereas, with the telepresence robot, she could meet the buddies ‘virtually’ or put on her Disney costume in the hospital room and be seen, heard, and included, which is the most important thing for her.

“Macy’s getting to that age where she’s aware of what she misses. So, for me, the biggest relief and drawcard in her using the robot, is being able to help alleviate some of her disappointment and to really support her emotional wellbeing.

“She’s such a motivated and driven child and takes everything in her stride, which we’re very, very lucky about. But, as a parent, it’s devastating to see her when she’s disappointed and tries to keep her chin up and get on with it, when you know she’s hurting.”

Looking ahead, Kate jokes Macy’s little brother, Charlie, aged two, will likely also want his own robot.

Charlie was an IVF baby with pre-implantation genetic diagnosis to rule out a one in four chance of him having or being a carrier of GACI after Kate and her husband, Jason, discovered they are “the one in a million couple”.

“We are two people who met, fell in love, and happened to each carry this very rare gene mutation… but we’ve only got one copy each and you need two copies of the gene to be symptomatic,” Kate says.

“So, when Macy first got diagnosed the question was asked if we could be related, when we’re actually just incredibly unlucky.”

In the past five years, Kate has become an expert on GACI. When Macy was 18-months-old, she helped launch advocacy group, GACI Global, aimed at remedying a worldwide lack of information and education about the condition.

She also credits HeartKids for providing invaluable information, alongside emotional support after Macy was first admitted to NICU with heart failure.

“For the first few years of her life, Macy’s dilated cardiomyopathy was her biggest problem,” Kate says of the Childhood-onset Heart Disease (CoHD) aspect of GACI.

“The coronary arteries which supply her heart muscle were incredibly small and calcified, so bits of the muscle were dying, and her heart essentially became big, weak, and floppy.

“It couldn’t contract properly and kind of just wobbled, and Macy still has effects of that with reduced left ventricular function… meaning the main chamber of the heart which pushes blood around the body doesn’t squeeze as well as in other children.”

One thing’s for certain in the Rawnsley family: “No one day is ever a given, and every day’s a blessing”.

Kate says: “We stay very optimistic and hopeful and just continue to live life presuming that Macy’s going to be with us long term, but obviously the risks are real, and things do change very quickly with her. We’re always looking for the next best treatment and what we can do, and how we can give her the best quality of life and the best longevity of life that we can.”

Importantly, she says this includes ensuring Macy doesn’t miss out on school life and associated social-emotional development.

“Macy’s a child who wants to learn and wants to be with her friends, so we can’t completely bubble wrap her. We need to give her the space and opportunities to create her own peer relationships, to play and explore.

“Obviously there’s lots of things the school community needs to be across in terms of understanding her symptoms and how to respond, and the adjustments that need to be made so she has continuous access to learning and socialisation.

“However, at the end of the day, we mustn’t forget that Macy’s a kid who wants to be a kid.”

It’s precisely why HeartKids and St Francis of the Fields Primary School have joined MissingSchool in launching the Australia-first National Insights for Education Directories (NIEDs), representing an alliance of organisations at the intersection of health and education.

Launched as part of Australia’s celebration of World Teachers Day (27 October), NIEDs takes the form of a groundbreaking one-stop digital hub. Importantly, it is designed to empower parents, carers and teachers with trustworthy just-in-time linkages, information and resources about health impacts on students’ connection to school, and what needs to happen to keep learning and wellbeing alive from anywhere.

NIEDs will unlock unique data, covering everything from teacher and parent insights to education system information contained in easily searchable digital directories of:

- 500+ medical, health, mental health, and support service organisations

- Australia’s public, independent, and faith-based schools; and

- Over 4,000 qualitative quotes and insights from parents and teachers

MissingSchool CEO and Co-Founder Megan Gilmour says:

“NIEDs is a gamechanger at the intersection of health and education putting reliable and actionable information in the hands of the widest support team for students facing complex health challenges.

The goal is to prioritise the learning and wellbeing journeys of these students alongside their peers by supporting their families and teachers at the point of pressing need.

Knowledge is indeed power… and so is presence.

Just as schools provide wheelchair ramps, they can also adopt synchronous telepresence technology. It offers students with medical absences continuity of classroom access, consistent curriculum, equality of opportunity, and learning alongside peers. Telepresence lets teachers teach lessons once. Telepresence cures absence.

All children should have equality of opportunity in education. All children should be seen and heard.”

HeartKids CEO Lesley Jordan says:

“In Australia, at least 1 in 100 school-aged children live with Childhood-onset Heart Disease (CoHD), which takes many complex forms and impacts every individual differently. The one thing they all HeartKids share is that the condition is lifelong, meaning school adjustments and teacher education is paramount, as is the commitment and flexibility to deliver a ‘normal’ school life for every student.

Currently, many children, teens, and young adults within the HeartKids community have no choice but to swap their classroom for hospital school, home study or no schooling at all. School absence differs from child to child, ranging from weeks to months, dependent on their treatment plans, surgical procedures or follow up.

This is why HeartKids is excited to join MissingSchool in launching NIEDs and driving the message home that continuous connection to school, teachers and classmates is vital to ensuring children don’t fall behind and reach their full potential in life.

We agree with MissingSchool that the COVID pandemic taught us the world can stay connected – remotely – during a health crisis. Further, we wholeheartedly support MissingSchool’s position that no different to what we’re seeing across workplaces in the post-COVID landscape, hybrid learning, utilising telepresence technology, is a feasible and flexible methodology to support and deliver education and keep children connected to school.

Based on years of experience supporting families across Australia, we also know that the better a school is informed and aware of how CoHD may impact learning and wellbeing – and the earlier the engagement – the better the experience for every child, family and school community.

In addition to sharing information and insights via NIEDs, HeartKids is also trialling a “Starting School” online information session as part of a new mental health program aimed at improving communication with schools and reducing anxiety of HeartKids parents and children alike.”

St Francis of the Fields Primary School Principal Tim Moloney says:

“Our school is preparing to welcome Macy and her parents to our school community next year. We have met several times to learn how we can best support Macy in her transition from Kindergarten. We have learnt a great deal about how resilient, intelligent and witty Macy is. One of the challenges for Macy is that she will require time away from school to cater for her health concerns.

Subsequently, Kate and the school are exploring opportunities to enable Macy to remain connected with her peers and teachers via telepresence robots. With the support from MissingSchool, who provide these robots, we anticipate that Macy will remain connected with her peers throughout each school day even while receiving treatment. It is my hope for Macy that the telepresence robot will enable Macy to enjoy academic experiences whenever she is able to; whilst building strong, loving relationships with her teacher and peers.

It is our job to cater for all.”

None of what we could do would be possible without the incredible support of you, dear reader, and our amazing MissingSchool community. We would always love to hear from you, so remember to stay in touch with us on social media, subscribe to our newsletter for helpful tips in supporting sick kids, and donate to help to build a future in which every child in Australia can be Seen and Heard.